Built between 1851 and 1876, the Victorian model village of Saltaire is located in Shipley, a commuter suburb and small town in the City of Bradford Metropolitan District in West Yorkshire, UK.

The name Saltaire is derived from the surname of industrialist, entrepreneur and philanthropist, Sir Titus Salt, who had the village built, and the River Aire which flows through it.

Every year, hundreds of visitors come to Saltaire to visit the village itself, and/or take a look round Salts Mill, the woollen ‘supermill’ that Titus Salt had built in the town. To do justice to both village and mill ideally takes (at least) a whole day. There is much to see and plenty of places where visitors can buy drinks, snacks or meals when required – both around the village and inside the mill.

Saltaire is situated by the River Aire, the Leeds and Liverpool Canal and the Airedale railway line, all ideal for the import of raw materials for Salt’s woollen mill and export of the manufactured goods.

Titus Salt cared about the welfare of the workers for his planned new mill on the edge of Bradford. He wanted to create a community in which they could live healthier and happier lives than they had in the slums of Bradford, where cholera epidemics were frequent. Saltaire was 3 miles from central Bradford and surrounded by open countryside with plenty of fresh air. In addition to these evident health benefits, Salt installed the latest technology in his mill, intending working conditions for his workers to be far better and safer than they were in mills elsewhere in the country. Undoubtedly, such improvements would also benefit output from his mill.

Salt employed local architects Henry Lockwood and Richard Mawson to design his new village. The first building to be finished in 1853 was the mill itself, while building work on the rest of the village continued until 1876.

When the mill opened in 1853, on Titus Salt’s 50th birthday, he threw a huge party for all his workforce. It was the biggest factory in the world, four storeys high and the room known as ‘The Shed’ measuring 600 feet in length. The mill employed 3000 workers and had 1200 looms. Over a period of twenty-five years, 30,000 yards of cloth were produced per day. The noise from the machines would have been deafening and the workplace very hot. Yet working conditions for employees in Salt’s Mill were still far better than in most other textile mills.

The following photos of the working mill were taken from a video playing inside the mill:

Salt’s enormous success in the textile industry was partly due to his use of the wool from alpacas. He combined it with other materials to create new varieties of worsted cloth. Wool worsted cloth as well as wool/cotton and wool/silk worsted cloths already existed for making men’s suits. In Salt’s day it was fashionable for ladies clothing. Most ladies would have wanted (but many couldn’t afford) expensive silk – and Alpaca made a light, smooth fabric with the lustre of silk, but was more affordable.

Architecture in the village was of a classical style, inspired by the Italian Renaissance. The rows of neat stone buildings were all terraced, arranged in a grid pattern. All streets were named after members of his family, such as Caroline Street after his wife. In total there were 823 houses, shops, a school, two churches, a school an adult education institute, park, hospital, and almshouses for the aged. The streets also had gas lamps. Each house had its own outdoor toilet – a luxury for the working classes in of the nineteenth century.

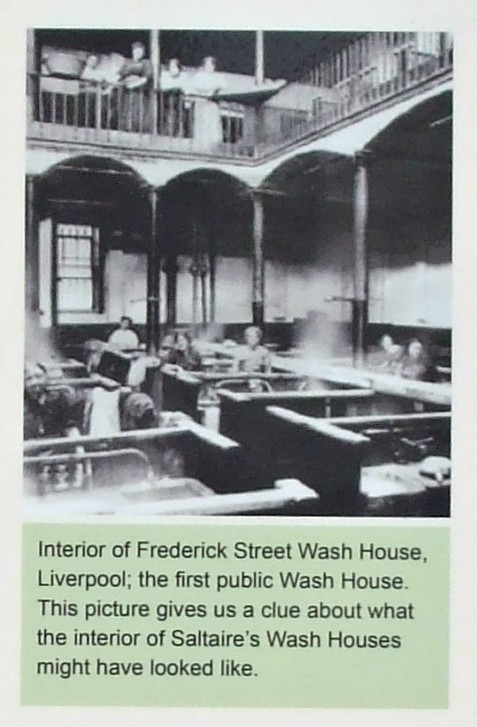

Salt also had a wash house and baths built in the village, the wash house because he objected to seeing lines of washing hanging in the back yards. Dirty washing could be brought to the wash house on Mondays to Thursdays. There were six washing machines powered by steam engines and four rubbing and boiling tubs using hot and cold water. Clothes were put through the wringing machine and dried in a drying closet before being mangled and taken home. The whole process took an hour.

There were 24 baths for public use with separate entrances for men and women. There was even a Turkish bath. The baths were open every day but Sunday from 8am to 8pm. Salt’s care for the health of his workers is evident but, unfortunately neither wash house nor bath house was popular and the building was converted into housing in the late 19th century. The houses were demolished in the 1930s and replaced by garages which were demolished in the 1950s. The site is now a small community garden.

Saltaire Congregational Church (now the United Reformed Church) was one of Lockwood and Mawson’s finest works and is set in a spacious landscaped garden. Salt was a staunch Methodist and insisted his workers attended chapel on Sundays. He also frowned upon gambling and the drinking of alcohol. A mausoleum beside the church is where Titus Salt was buried.

The Victoria Hall is also worth a look inside:

Robert’s Park, alongside the River Aire is a pleasant, open space to spend a little time. The alpaca statues are a reminder of the importance of their wool to the continuing success of Titus Salt, whose statue is also in the park.

Salts Mill closed as a textile mill in 1986 and was bought the following year by Bradford entrepreneur, Jonathan Silver who had it renovated. Today it houses a number of business, commerce, leisure and residential concerns. The main mill is now an art gallery, shopping centre and restaurant complex. There is a fish restaurant and Salts Diner, a cafe which serves a variety of dishes.

The 1853 Gallery takes its name from the date of the building in which it is housed and it contains many paintings by local artist David Hockney. A bust of Titus Salt welcomes visitors through the door.

Today, Saltaire is a popular place to visit, as an educational experience or simply e a lovely village in which to spend some time. Families come for many reasons, and boat rides along the canal seemed popular on the day we were there. Oddly enough, one of the boats was called Titus. I wonder why…

World Heritage status was bestowed upon Saltaire in 2001. It is described on an information board in the village:

Our visit to Saltaire was three years ago now. We had planned to go back again sometime this year. But as they say, ‘All the best-laid plans of mice and men…’ Perhaps next year, then…

Refs:

- Information boards around Saltaire

- Wikipedia

- My Learning

The fleas that live in the rat’s fur are carriers of plague bacilli and when they feed on the rodent’s blood they leave the bacilli in its body, causing rapid death. If the number of rats plummets, infected fleas will take the blood of humans or other small mammals.

The fleas that live in the rat’s fur are carriers of plague bacilli and when they feed on the rodent’s blood they leave the bacilli in its body, causing rapid death. If the number of rats plummets, infected fleas will take the blood of humans or other small mammals.

=

=

![Stall selling garden produce front of workhouse Stall selling fruit and veg at the front of the workhouse and]gardens](https://i0.wp.com/milliethom.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/stall-selling-garden-produce-front-of-workhouse.jpg?w=249&h=249&crop=1&ssl=1)