This is the third and final part of my post about Kenilworth Castle (which I started with every intention of finishing in a single post!). So before I plough on, here is the map, showing where Kenilworth Castle is located in the U.K.

And this is the plan that shows the growth of the castle between the 11th and 16th centuries:

I finished Part 2 with the work completed by Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, in the 16th century, and in this post I intend to look at what happened to Dudley’s fabulous castle (plan below) in the years following his death until the present day.

I finished Part 2 with the work completed by Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, in the 16th century, and in this post I intend to look at what happened to Dudley’s fabulous castle (plan below) in the years following his death until the present day.

Having no legitimate heir, on Dudley’s death Kenilworth Castle passed to his brother, Ambrose. However, family wranglings over ownership gave James I the opportunity to take the castle back into Crown hands in 1603. In 1611, King James’ son, Prince Henry, agreed to pay huge sum of £14,000 for full title to the castle. On his death the following year, Kenilworth passed to his brother, Charles: the future Charles I. The buildings were well maintained, and several royal visits took place, until the outbreak of the Civil War in 1642.

Following the Battle of Edgehill in October 1642, King Charles withdrew the Royalist garrison from Kenilworth. The castle was occupied by Parliamentarians and remained largely untouched for most of the Civil War. But the uprisings of 1648 and the imprisonment of Charles I, brought about a change in Parliament’s attitude to all former Royalists strongholds. In 1650 Kenilworth was slighted (cannoned) along with many other castles across the country. All buildings in the Inner Court were severely damaged leaving Leicester’s Gatehouse along the Outer Curtain Wall the only building to remain intact.

This photo of a reconstruction drawing shows the possible state of the castle between 1650-60 following the slighting. The mere was also drained at this time and the Inchford Brook returned to its natural course through a culvert in the dam. (A culvert is a tunnel carrying a stream or open drain under a road or railway.)

The castle and estate were acquired by Colonel Joseph Hawkesworth, the Parliamentarian who had overseen the slighting. He had Leicester’s Gatehouse turned into a residence for himself with a farm in the Base Court. Fellow officers divided the estate into farms and pillaged the castle’s buildings in the Inner Court for their building materials. Hawkesworth had the passageway into which coaches would enter the building blocked and the space converted into a hall/dining room. He also added a gabled extension, which became the kitchens and where the wooden stairs up to upper floors can be found. A classical porch was added to the west of the building, too.

With the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, Hawkesworth was evicted and the castle restored to Charles’ mother, Henrietta Maria, and for a short time, the stewardship of the earls of Monmouth. It continued to pass through a number of nobles over the next two hundred years until it came to Thomas Villiers who became Earl of Clarendon in 1776. Kenilworth remained with the earls Clarendon until 1937. Their tenants lived in Leicester’s Gatehouse using the buildings in the Base Court as a farmyard.

By the later 18th century, tourists had begun to take an interest in the ruins and the first guidebook was published in 1777. But by the start of the 19th century, the buildings had been allowed to seriously decay, and in 1817, thirty tons of stone crashed down from the north-west turret of the Great Tower/Keep, making it a very unsafe place to visit.

The Great Tower today:

In 1821, Sir Walter Scott published a romantic novel titled, Kenilworth, which generated huge public interest in the castle. The novel tells of the sudden and suspicious death of Amy Robsart, Dudley’s first wife, against the backdrop of Queen Elizabeth’s famous visit to Kenilworth in 1575 – despite the fact that Amy died in 1560. After the book’s publication, Kenilworth Castle became a major tourist attraction and by the time Scott returned to the castle in 1828, he found it much better preserved and protected.

In 1821, Sir Walter Scott published a romantic novel titled, Kenilworth, which generated huge public interest in the castle. The novel tells of the sudden and suspicious death of Amy Robsart, Dudley’s first wife, against the backdrop of Queen Elizabeth’s famous visit to Kenilworth in 1575 – despite the fact that Amy died in 1560. After the book’s publication, Kenilworth Castle became a major tourist attraction and by the time Scott returned to the castle in 1828, he found it much better preserved and protected.

This 19th century photo (also used as my featured image) shows John of Gaunt’s Great Hall as a pictuesque, ivy-covered ruin. it is believed that the ivy was killing the deterioration of the medieval building.

This idyllic scene showing the whole castle as an ivy-covered ruin, was painted by James Ward in 1840:

Substantial clearance of rubble and some restoration work was done in 1860 and more in the late Victorian era, including the rebuilding of lost walls, but by the 1920s, the 6th Earl of Clarendon was finding it difficult to pay for all the maintenance. Fortunately, in 1937, the castle was purchased by Sir John Davenport Siddeley, a pioneer of the motor industry and later 1st Baron of Kenilworth. In 1938, he placed it in the hands of the State and gave a large sum of money towards the cost of repairs. Since 1984, Kenilworth Castle has been managed by English Heritage.

Leicester’s Gatehouse was lived in until the 1930s and today’s visitors can see the ground and first floors decorated and furnished as they would have been then. The top/third floor houses a display depicting Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester and Queen Elizabeth’s last visit to Kenilworth in 1575. There are also information boards and photographs showing Siddley’s career and the vehicles produced by him from the early 20th century until his death in 1953.

There are two ground floor rooms, one being the dining room, the other the southern or south room. The rather blurry photo is of the dining room in the 1930s and the small gallery shows some of those same pieces of furniture that are still in the room today:

The southern room is approached through the wooden screen shown on the photo in the gallery above. This room contains an alabaster fireplace and Elizabethan panelling that were relocated here from Leicester’s Building some time after 1650. The fireplace bears the initials ‘RL’ and the date 1571.

This photo from Wikipedia gives a close-up of the initials of Robert Dudley which are barely visible in my photo of the fireplace:

These are photos of the wooden stairs and first floor bedrooms:

Finally is the top/third floor of Leicester’s Gatehouse and a few photos from the information boards about Sir John Davenport Siddeley’s career and some of the vehicles produced by the Armstrong Siddeley Company over the years, which included aero engines and airframes. Sir John died in 1953 and car production ceased after 1960 but the aviation side of the business continued. I particularly like the last photo in the gallery which shows one of Siddley’s cars from 1925, with Kenilworth Castle in the background.

I set out to write a single post about Kenilworth Castle – and now there are three. I seem to have got a bit carried away but I enjoyed reminding myself about a lovely visit we had to Kenilworth in 2017 and of its amazing history. The restoration work done by English Heritage is wonderful and ongoing, and the Elizabethan Garden they created is lovely.

The photo below shows a plan of Kenilworth Castle as it appears today: an extremely interesting and safe environment for visitors.

Key to map: 1. Mortimer’s Tower 2. Old Stables (Cafe and Information) 3. Leicester’s Gatehouse 4. Base Court 5. Great Tower 6. Inner Court 7. Great Hall 8. Leicester’s Building

*

References:

English Heritage Guide Book: Kenilworth Castle

Information boards around the site

Various online sites including: English Heritage website, Historic UK and Wikipedia

Hesketh Park is located at the northern end of Lord Street, Southport’s most famous street, and just a mile away from the town centre. It was created in 1868 by Edward Kemp on land donated by the Reverend Charles Hesketh of Meols Hall, which I’ll be talking about in my post on Southport in general.

Hesketh Park is located at the northern end of Lord Street, Southport’s most famous street, and just a mile away from the town centre. It was created in 1868 by Edward Kemp on land donated by the Reverend Charles Hesketh of Meols Hall, which I’ll be talking about in my post on Southport in general.

The Deep is a public aquarium in the city of Kingston-upon-Hull (often referred to simply as Hull) in East Yorkshire, and it’s a great place for a family day out.

The Deep is a public aquarium in the city of Kingston-upon-Hull (often referred to simply as Hull) in East Yorkshire, and it’s a great place for a family day out.

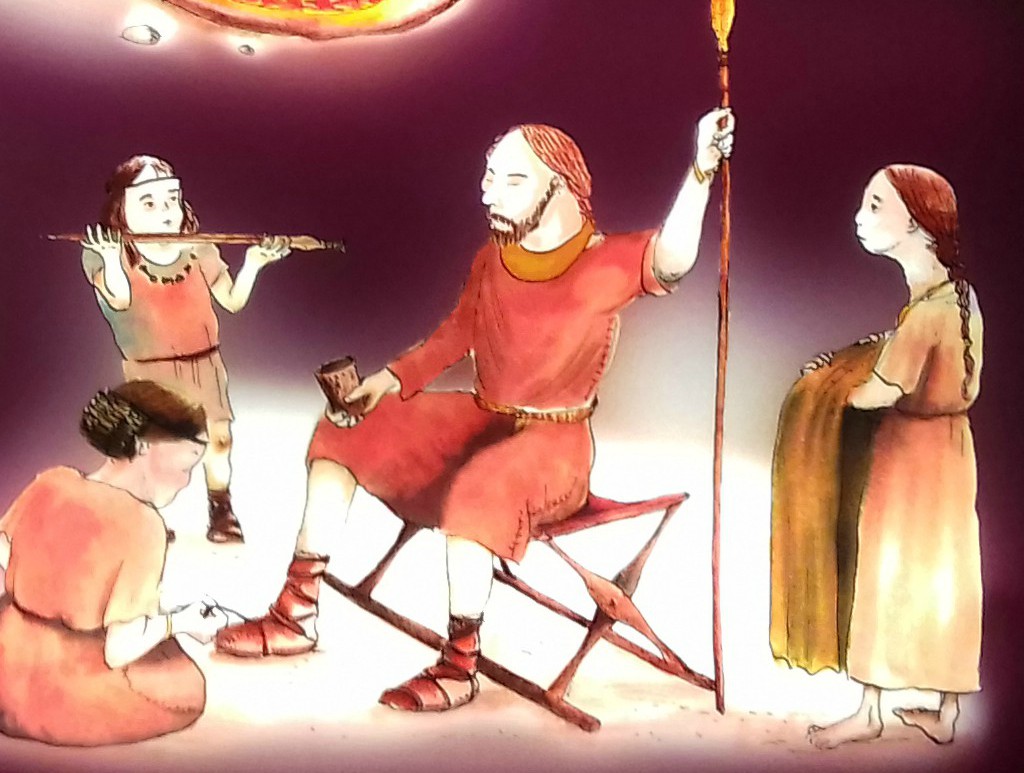

The first display is The Awakening Earth, which comprises hands-on activities and 4D screens showing creatures that would have been swimming around in the oceans up to 400 million years ago. These included Dunkleosteus (370 m years ago) Ichthyosaur (240 m years ago) and Xiphactinus (80 m years ago).

The first display is The Awakening Earth, which comprises hands-on activities and 4D screens showing creatures that would have been swimming around in the oceans up to 400 million years ago. These included Dunkleosteus (370 m years ago) Ichthyosaur (240 m years ago) and Xiphactinus (80 m years ago).