This is my third post about King John, and I just thought that, having written about the 800th anniversary of his signing of the Magna Carta, it could be useful to have a look at the reasons why the barons decided that such a charter was necessary. Was John really that bad…?

King John has the worst reputation of any English king. Other kings were seen as incompetent (Henry II) some as cruel (Richard III) but to his contemporaries, John was seen as both. It is true that most of the sources that condemn his actions were written by monks -and John was no friend of the Church – but his reign was obviously bad enough to lead to one of the most famous documents in history: the Magna Carta.

‘He feared not God, nor respected men.’ (Gerald of Wales)

‘A pillager of his own people.’ (the Barnwell annalist)

Just how true are these quotes?

John’s problems seem to have started on the day he was born…

John was born in Oxford on Christmas Eve, 1167, the last of the four children of King Henry II and the formidable Eleanor of Aquitaine.

As such, he lived in the shadow of his older brothers: Henry, Geoffrey and Richard. At an early age he was given the nickname of ‘John Lackland’ because, unlike his elder brothers, he received no land rights in the continental provinces and was never expected to become king.

As a young man, Prince John was notorious for events during his role of Lord of Ireland. He squandered his money and offended Irish lords by mocking their unfashionably long beards. Then, in 1189, he broke his father’s heart by siding in a rebellion against him. On Henry’s death, since his two eldest sons had died by this time, Richard became the next king. All of Henry’s lands went to Richard, thus continuing his nickname of ‘Lackland’.

John was forever in Richard’s shadow. Richard was loved and respected by his subjects and his men, and famous for glorious deeds across the known world.

John could never compete. Richard even forgave John for rebelling against him and gave him To assure Richard of his newfound loyalty, John went to Évreux in Normandy and took a castle. Unaware of John’s reconciliation with Richard, the garrison thought he was still allied to King Philip of France and accepted him. John massacred them all.

So John already had a reputation for treachery before he became king – a reputation that worsened after Richard I was killed by a crossbow wound in 1199 and John took the throne.

His reign started reasonably well, although many incidents soon occurred. War broke out with France again and King Philip supported 16-year-old Arthur of Brittany against John. As the son of John’s elder brother, Geoffrey, many believed Arthur was the rightful heir.

There are sources that suggest that John was responsible for Arthur’s death. Some maintain that John killed him in a drunken rage and dumped his body in the River Seine; others say that Arthur died after being castrated. However the boy died, it is believed to have been at John’s hands.

John was always at loggerheads with the Church, one incident being particularly noteworthy. This was over John’s protest at Pope Innocent III’s choice of Cardinal Stephen Langton as Archbishop of Canterbury. In 1208, the pope placed the whole of England under papal interdict. Church services and sacraments were suspended across England (except for baptism and extreme unction). Bodies were buried in woods, ditches, and by the side of the road. Only two bishops remained in England. The following year, the pope excommunicated John from the church.

John raked in money during the interdict, exploiting the weakened Church and amassing the huge sum of over £65,000 (£30 million in modern money). But the interdict also encouraged John’s enemies. King Philip of France planned an invasion in 1213 with papal blessing. As John wanted Rome on his side, he dramatically submitted to Rome and accepted Langton as Archbishop of Canterbury. And a surprise attack by English naval forces in May, 1213, ended Philip’s threat.

During the interdict, John had been free to impose his dominance over the British Isles. He made the old Scottish king accept costly and humiliating terms. In 1210, he led a force of 800 men to Ireland to quell an open rebellion against him led by powerful lords such as William Marshal, William de Braose and the de Lacy Brothers – who were protesting at John’s financial and political demands for funds in his campaigning in France. The barons submitted or fled. In Wales, Llywellyn the Great also rebelled, but faced with John, he retreated into the hills of Snowdonia and agreed to harsh terms.

The act that one historian described as ‘the greatest mistake John made during his reign’ involved John’s heinous treatment of the family of William de Braose.

The rebellion in Ireland gave John the excuse he needed to go after a personal enemy. De Braose had been John’s right hand man for years. In 1201, John offered him the honour of Limerick in Ireland for 5,000 marks. Six years later, de Braose still owed most of the money. After the rebellion in 1210, de Braose fled to France, but his lands and his wife, Matilda, and his son were still in Windsor Castle. John moved them to Corfe Castle in Dorset and threw them in the dungeon, where he let them starve to death … perhaps his most notorious and malicious act. One chronicler reports that the bodies were found with the mother slumped across her son, with her head lying on his chest. She had been gnawing at his cheeks for food. Rumours circulated that John had killed them because they knew the truth about Arthur of Brittany’s death. William de Braose had been with John at the time of the boy’s disappearance.

Many of the barons did not feel safe after the de Braose affair. They also had many, accumulated grievances regarding financial burdens, the nature of John’s rule and penalty system and personal grievances about his notorious womanising and taking mistresses – even the wives and daughters of powerful men. The final straw came after John’s long-awaited attack on France ended in defeat and John returned, demanding even more scutage from them…

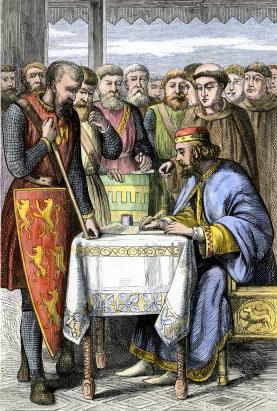

In 1215 the barons broke homage to John and formed the Army of God and the Holy Church – a declaration of war on the king. They offered the crown of England to Prince Louis of France, King Philip’s son and heir, if they would cross the Channel with an army to help them. On the 17th May, the barons seized the capital of London and drew up their demands in a document originally called the Articles of the Barons. It was the first draft of what later became known as the Great Charter – the Magna Carta.

By October 1215, after the signing/sealing of the Magna Carta at Runneymede in June – a treaty that John had no intention of keeping – war with the barons resumed. In May 1216, Prince Louis of France invaded with a powerful force in support of the English barons who had wanted him crowned king in place of John. John spent the rest of his reign trying to regain control of his kingdom. At Lynn (now King’s Lynn) in October he fell ill, possibly of dysentery. On October 11th he led his army on a short cut across The Wash at low tide – a disastrous move. Whether due to the returning tide or the quicksand there, his baggage train and treasure were lost beneath the waves. This was the last disaster of a disastrous reign.

John’s health rapidly deteriorated and he headed for Newark Castle on a litter, reportedly ‘moaning and groaning’ that the journey was killing him.

On arrival he confessed his sins and received Communion for the last time. He died on the night of 18/19 October in the middle of a great storm.

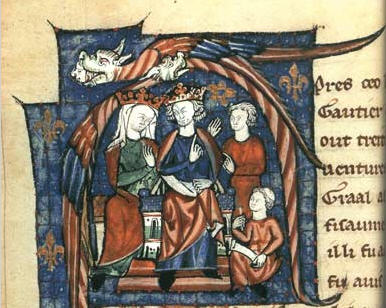

*Note: The header image shows John of England (John Lackland) by Matthew Paris from his Historia Anglorum, 1250-59. British Library royals MS. Public Domain.