The Second Battle of Lincoln – or the Battle of Lincoln Fair– took place during the First Barons’ War on the 20th May 1217 at Lincoln Castle in Lincolnshire, England. As 2017 marks the battle’s 800th anniversary, it is being commemorated by reenactments of the battle itself together with accompanying activities for locals and visitors to enjoy. One of these extra attractions is the Knights’ Trail, which involves people finding 37 very colourfully painted models of mounted knights, all placed at prominent spots around central areas of the city.

Last Sunday (21st May) we went along to have a look at preparations for the battle and a general potter about at the castle. This Sunday (28th May) we headed off to watch the re-enactments of the different engagements involved. Needless to say the castle and surrounding areas were packed, particularly in the afternoon.

This was understandable for several reasons. Firstly, it was Bank Holiday weekend and the start of the half-term break for schools. Consequently, many families were out and about keeping children entertained as they usually are at such times. Secondly, people came to Lincoln over this particular weekend because the Domesday Book (compiled 1085-86) and Charter of the Forest (1217) were both on display along with the Magna Carta – which is resident there anyway, on loan from Lincoln Cathedral – inside the Old Prison which is in the castle bailey:

Both are incredibly important and precious documents, and although no photography was allowed, it was still wonderful to see them. The two documents will be in Lincoln throughout the summer.

The weather was pleasant with bursts of sunshine, and everyone seemed to be having a great time. We got there around 10.30 am and had a walk round the bailey, generally ‘having a look’ at the encampment of the reenactors and various items and activities going on before the first part of the battle began. These are a few photos from around the camp. Lots of knights were about at this point, too:

The events leading up to this battle are very much linked to King John, who had died the previous year (October 1216). John had been a very unpopular king for many reasons, most of which were based on his inability to rule wisely, as well as his questionable personality traits. When he died he left his son as king – the nine-year-old Henry – with the formidable William Marshal, the earl of Pembroke, as his regent.

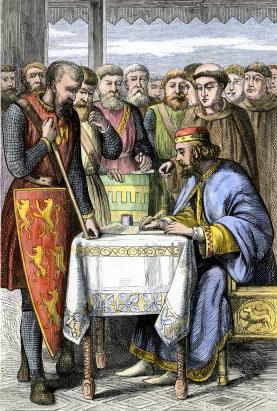

Some of the barons who had rebelled against John during his reign and forced him to sign/seal the Magna Carta, had already taken steps to put the French Prince Louis (the future Louis VIII) on the English throne. On John’s death, a few of the barons returned to the loyalist side whilst others pushed on with their intentions of crowning Louis in order to stop John’s son from ruling. The kingdom was deeply divided over this.

Twenty-year-old Louis and his French armies had been in England since May 1216 and by May 1217, aided by the rebel barons, controlled half the country: only Lincoln and Dover castles had not surrendered. At the time of the battle at Lincoln Castle, the city itself was occupied by forces fighting for Louis, led by Thomas, the Comte du Perche. But the castle was steadfast. Lady Nicola de la Haye, the castellian, remained true to the royalist cause and was determined to keep this castle, with its strategic position, out of rebel hands.

During the day, we watched three different events that took place at Lincoln. The first showed the arrival of the French at Lincoln and their attack on English defenders beneath the castle walls. The English are pushed back and those still alive flee up to the safety of the castle. The Comte du Perche, conspicuous with his shield displaying three chevrons, warns his men to be nice to the citizens of the city and pay for all their food and drink. It’s important to keep the people ‘on their side’!

The second reenactment showed the attack on the Lucy Tower/Lincoln Castle using two different siege engines. One of these was the perrier – one of the least complicated of medieval siege engines It consisted of a simple frame with a huge 17 foot throwing arm with a sling. Some perriers are recorded as needing as many as 16 men to pull the ropes. It was the forerunner of the trebuchet, which has a large swinging arm to hurl missiles at the enemy and a counterweight to swing the arm. This very short clip shows the two siege engines being used on the day. The first we see is the trebuchet:

The Comte du Perche sees the bombardment as a great success, as parts of the castle walls begin to crumble.

The third engagement – the actual Battle of Lincoln Fair – followed the arrival of reinforcements for the English, led by the formidable, 70-year-old William Marshal, the earl of Pembroke and regent to the young King Henry III. This was him as he delivered his his speech about his life and duties to the Crown to the crowds earlier in the day:

Marshal had roused his loyal barons from across the country and ridden to Lincoln. The arrival of his army, together with the steadfast hold on Lincoln Castle by Lady Nicola, proved to be decisive factors in the defeat of the rebels – and the end of their attempt to put a French prince on the English throne.

We attempted several videos of this battle but, unfortunately, there were so many spectators (and we got there too late after lunch!) to grab a good spot for photography. I managed to squat on the grass near the front – until these to two delightful little boys with buckets on their heads – in reality, replica battle helms – decided to take the space in front of me:

I eventually managed a few photos during this battle, some of which show Lady Nicola taking stock of events from the gateway of the Lucy Tower:

I eventually managed a few photos during this battle, some of which show Lady Nicola taking stock of events from the gateway of the Lucy Tower:

Nick managed to film part of the battle, before people walked in front of him. It’s not too wonderful ‘ He missed Marshals’ rallying speech to his army, and the film had to be cut before the end, but it gives a general idea of events. The English come in from the left on this one, and William Marshal is on horseback.

Following this short clip, English soldiers come up behind the French. Caught between two attacking armies, the rebels are soon overwhelmed. Thomas, Comte du Perche, is shown being cut down in the arena – contrary to the 13th century drawing by Matthew Paris which shows him being shot down by a crossbowman as he fled from the castle. But, whatever happened, the comte obviously died that day.

Following the battle, Marshal’s soldiers ransacked the city that had welcomed and supported the French. Most Lincoln people had hated King John and welcomed the possibility of a new king from France. Marshal’s army used that as an excuse to pillage at will as they celebrated their triumph over the combined armies of the French and rebel English barons.

And thus we have the name of The Battle of Lincoln Fair: a celebratory post-battle ‘free for all’ for William Marshal’s victorious army.