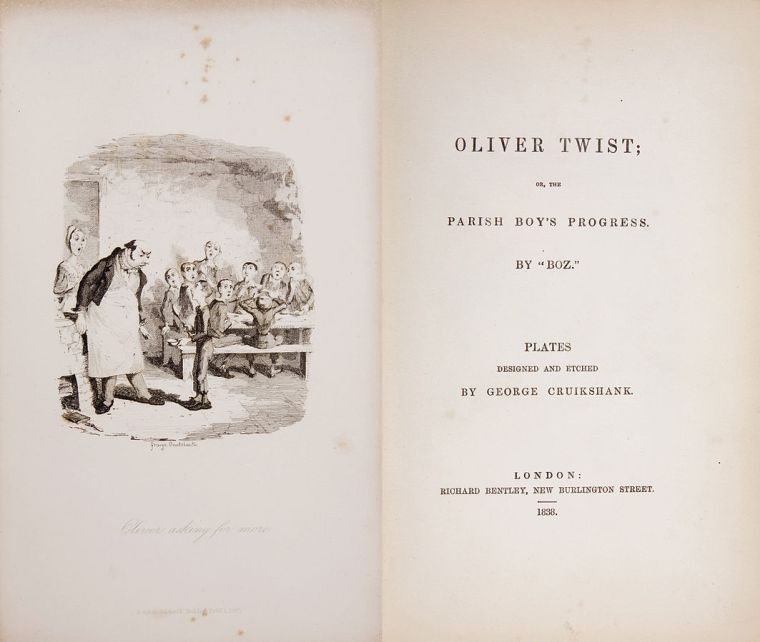

Anyone who has read Dickens will have heard of ‘the workhouse’ and the fear it struck into the hearts of some of the poorest people in society. Although the initial intentions of setting workhouses up may have been admirable, stories about just how harsh, strict, austere and, in some cases, cruel, these places were still linger today.

So what, exactly, were these ‘workhouses’, when were they set up and why?

In the early 1800s, the rising cost of caring for the poor and elderly in their own homes was unpopular with ratepayers. It was Reverend Becher in the town of Southwell in Nottinghamshire, who devised a new system to cut these costs.

A network of hundreds of specially designed workhouses, 15-20 miles apart, was set up across the country as part of the most ambitious welfare construction ever attempted in Britain: the New Poor Law of 1834. Workhouses were places where the poorest people in society had to work in return for food, shelter and medical care. Life inside was intended to be basic and dull, so that only those people in real need (paupers) could find shelter there, while those who weren’t destitute wouldn’t ask for help, knowing they’d be sent to the workhouse.

The people who set up the Poor Law didn’t intend to be cruel, only fair and efficient, yet workhouses were an odd combination of care and deterrence. ‘Inmates’ were fed, housed and clothed, but the stigma on those who went there, together with the hard, tedious work and sometimes, corrupt staff, ensured workhouses were places of last resort. They not only catered for the most poor, but also for the elderly without work, deserted wives, unmarried mothers, children without parents and those with physical and/or mental disabilities. They also took in vagrants/tramps and offered them a meal and a bed for the night. Altogether, the Workhouse at Southwell could accommodate 158 paupers.

In the model of the Southwell workhouse below, we can see how the ‘wings’ to either side of the central section separated the men women and children – something so hard for most families to bear. The central area largely provided accommodation for the Master and Matron, with the children’s dormitory and schoolroom on the very top floor. Later on, a new schoolroom was built attached to the workhouse and can be seen to the far left of this model. Men were housed in the wing to the right of the front door (blue in the model) and women in the (yellow) wing to the left:

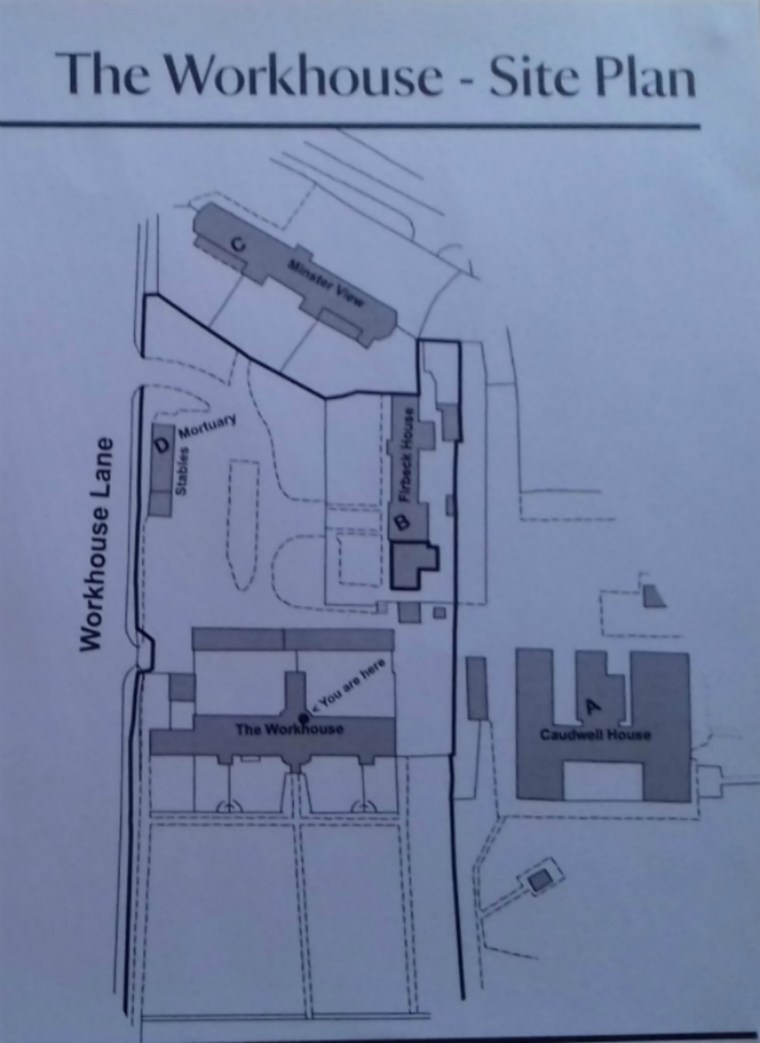

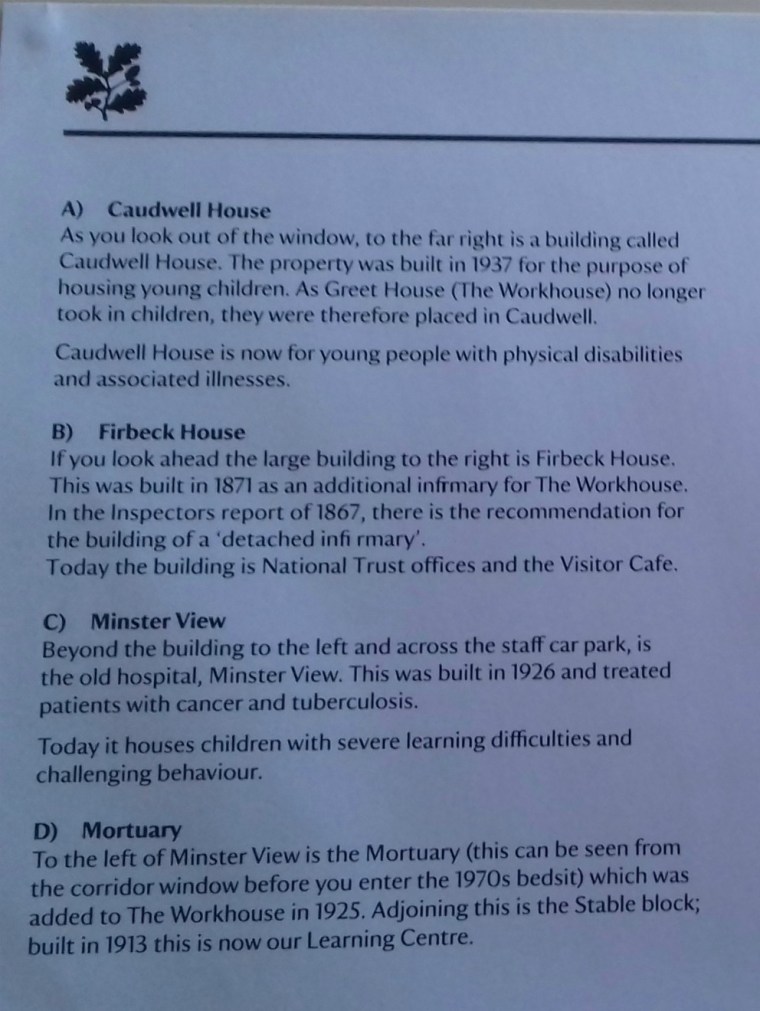

The plan below shows the layout of the site and the notes explain a little about different areas:

The workhouse staff was headed by the Master, who reported to elected Governors who were answerable to the taxpayers. The Master, who was often seen as cruel and corrupt, had responsibility for the day to day running of the house. The most important woman in the workhouse was the Matron, who would simply have been the Master’s wife in the earlier years of the system, with no formal qualifications. As nursing standards rose, things changed, and later matrons were expected to have the necessary nursing qualifications.

The Schoolteacher’s job was not an enviable one and the turnover of teaching staff was high. Schoolteacher’s were badly paid and of low status, despite high standards being expected from them by the school inspectors. It was usually a live-in job which involved supervising the children throughout the day as well as instructing them in the classroom. The Guardians abolished the Workhouse school at Southwell in 1885, and children were sent to local schools instead.

On entering the Workhouse, all new inmates were bathed and given the workhouse clothes/uniform to wear:

- Inmates were also categorised, with future treatment and daily workload in mind:

- Able bodied (separate groups for men and women)

- The old and infirm (also separate groups)

- Children

1. Able bodied men and women were called ‘idle and profligate’ or, ‘the undeserving poor’. These people were considered to be physically capable of work but were not employed due to their own idleness, incompetence or lack of training – although it was often due to the general levels of unemployment and scarcity of work and not their own fault at all! Consequently, jobs in the workhouse for these people were hard and were what gave the workhouse its name. One of the jobs for able-bodied men was splitting rocks (or old bones for fertilizer) out in the men’s yard at the back of the workhouse. They could also be given decorating duties, turning a mill handle and digging in the gardens.

Able bodied women generally came to the workhouse due to loss of a husband, or because the husband was out of work or she and a low-paid husband could not afford to keep a large number of children. These women did all the everyday housework, including cleaning the building and scrubbing stone floors, meal preparation and back-breaking clothes washing – which was done in buckets or bowls at the pump in the yard at first, then inside the ‘wash house’ once it was built:

Women also did needlework (e.g. lace-edged doilies for selling) and knitting.

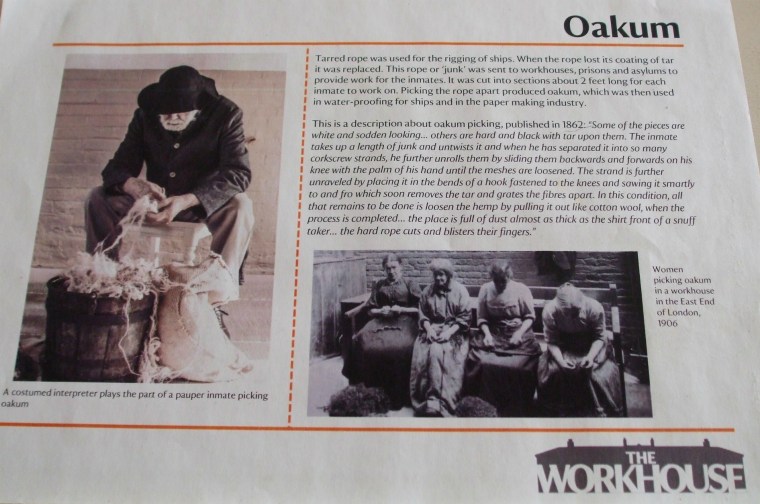

2. The old and Infirm were also called the ‘blameless’ or ‘deserving’ poor. They were people who could no longer work due to age-related disabilities. Younger people with disabilities were also in this category. Any elderly who were able to work could be given the task of picking oakum (old tarred rope) which was then sent to be made into caulking for ships. Oakum picking was a job that any groups could also be assigned to and was very hard on the fingers.

3. While the adults were working the children would be ‘educated’, which involved 3 hours a day in the schoolroom followed by what was called ‘industrial’ work: boys often worked in the gardens while girls did needlework and cooking. Children were allowed time to play in the little playground of the schoolhouse, and a large number of hoops were recorded as being ordered. Other toys came from local benefactors.

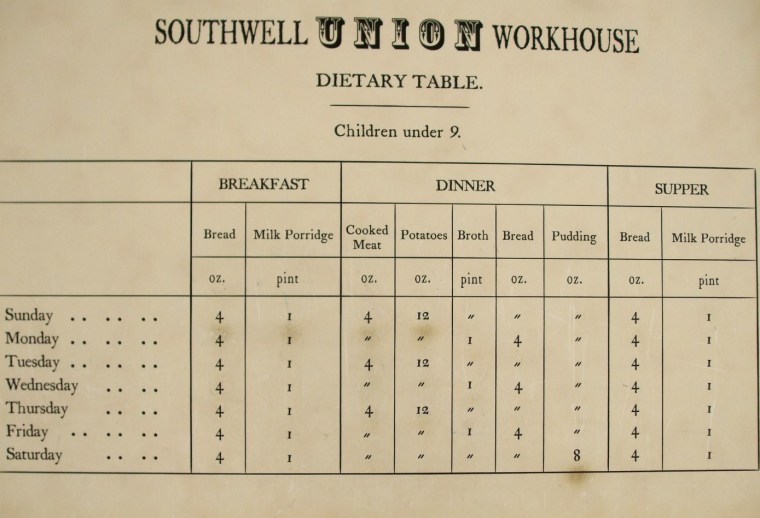

The main meal of the day at Southwell was dinner at midday, for which inmates were given one hour. This meal consisted of boiled meat, peas and potatoes on most days with soup on others. On Saturday a simple suet pudding was served. Although bland, the food was better than what these people would have had before they came to the Workhouse. Weekly and daily allowances/rations of different foods were strictly observed as lists around the kitchen areas show:

The Workhouse rules were strictly adhered to and anyone who broke them was punished. Punishments were different for different offences, but often involved limiting food rations, offenders typically being given potatoes, bread or rice instead of the usual meat. Repeat offenders were given solitary confinement for 24 hours and severe cases of injury to others for example, were sent to the magistrate.

These are some of the many photos we took of different areas outside the Southwell Workhouse (including a couple taken through upstairs windows):

And these are just a few of the dozens we took inside the workhouse:

By the late 19th century the focus in workhouses had changed from that of deterring the able-bodied to providing shelter and nursing for those who could never be in work. Consequently, the numbers of inmates and staff changed. In the earlier days at Southwell, the ratio between the two was an average of 4 members of staff to 135 inmates. By 1900 it had become fewer than 80 inmates to the 135 staff, plus a porter, a nurse and assistant nurse. Seamstresses, laundry maids cooks and gardeners soon followed – all doing jobs formerly done by inmates. New, more comfortable furniture was brought in, chamber pots replaced earthen closets, and eventually flushing water closets. A new infirmary building was added in 1871 and by 1905 children were being housed in separate homes or were boarded out. In 1913 workhouses became ‘institutions’, though most adopted less stigmatised names: the workhouse at Southwell, for example, became Greet House, named after the river that runs below it.

The 20th century saw huge changes in the ways the poor, the elderly and people unable to work were treated. The Welfare State, which came into being in 1948, brought financial benefits and healthcare to many people. Many former workhouses were taken over by the new National Health Service as state hospitals, and at Greet House elderly patients were moved out of the old, Victorian building into the two infirmaries – one for men, one for women – while the old building housed staff and provided kitchens for cooking residents’ food. Until 1977, the former ‘women’s wing’ of the workhouse was used as temporary ‘bed-sit’ accommodation for homeless mothers and children awaiting more permanent housing. The last residents moved out in the 1990s when a new home was especially built. This is how the ‘bedsit’ looks today:

The Work house at Southwell was left derelict for some time and fell into disrepair until 1997 when the National Trust recognised it as being ‘the best preserved workhouse standing in England and well worth saving’.

Refs: Most information taken from the book purchased, free leaflets and the information boards at the Workhouse in Southwell.

![Stall selling garden produce front of workhouse Stall selling fruit and veg at the front of the workhouse and]gardens](https://i0.wp.com/milliethom.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/stall-selling-garden-produce-front-of-workhouse.jpg?w=249&h=249&crop=1&ssl=1)

Millie a wonderful post that broke my heart. Mans inhumanity to man. It made me think of what is happening under different cover today. Our secretary of health and human services force resignation for using elite travel on the taxpayers money rob the tune of a million dollars while our government attempts to pass a cruel and harsh healthcare bill for the citizens.

Thanks, Holly. The Workhouse is one of those places that seems to hold memories in its walls – so much hardship and suffering, as you say. It often seems as though we haven’t moved on a great deal since Victorian times and I know exactly what you’re saying about things happening where you are. We have so much to moan (and worry) about over here, too.

That’s a fascinating look back Millie. History can be horrifying.

As you say, a laudable idea to hep the poor prior to Welfare, but it didn’t quite work out. Great photos, it looks like a very interesting place to visit!

It is interesting, Ali, and there are so many personal stories to take in. We’ve been there twice now, and on this occasion Lou came with us. She has lots of great photos that will probably appear on her posts from time to time. If you’re ever up this way, it’s well worth a visit.

Millie, a fascinating post and very well researched and written. The workhouses were stark grim places where so many died…your photos give a real sense of the place. I had no idea there were any open as a museum and if I’m in the area a place I want to visit.

Hi Annika, thank you for liking my post. I’m not sure whether there are other workhouses open to the public. This one was taken over by the National Trust because it was already in a good condition. It was an important one, too, because it was a pioneer of its kind – probably because the man who thought up the idea of the poor and destitute being housed together came from Southwell. It’s certainly worth a visit if you’re ever in the area between Newark and Nottingham. I’ts less than a half hour drive for us.

What an extraordinary slice of grim history. Thanks for all your work to bring us such an excellent overview.

Thanks Peggy. So much about the Victorian era was grim – unless you were rich, or comfortably off, at least. It might have been a great time for industrial and agricultural development and improvement, but it was pretty miserable for the poor. Workhouses would have seemed like prisons to the destitute, and in that workhouses took away their freedom, in many ways they were. It’s a sad but interesting place to visit.

Excellent post, Millie. It does remind me of Dickens too. Let’s have faith our future as a society will be brighter. Best wishes, MG.

Thanks, MG. You’re right, we all need faith that our future will be brighter and better for everyone. What good is ‘progress’ if it isn’t? Dickens portrayed Victorian society and its values so well.

Never heard about it before. Thanks for the wonderful post Millie

I’m glad the post was informative for you, Arv. Workhouses were pretty miserable places, but when the alternative was to starve to death in a squalid home, many of the poorest people had no choice. The shortage of jobs for the unskilled was a big problem at that time. Not all of those out of work were ‘idle and profligate’. Thank you for reading!

It is really to hear about it, Millie. And thanks for the lovely information.

I love Charlie Dickens, but his books are full of tragical heroes and their stories. This place looks the same as I imagined. You made me think a lot!

Yes, Dickens seemed to focus on stories of the poor and destitute. Workhouses were a part of Victorian life, so I suppose they were bound to come into stories written at that time. Thanks for visiting, Ann.

This is such an interesting and sad post. You provided a glimpse into history I was not aware of. How disheartening!

Thank you, Antonia. The Victorian era was hard on poor people. There were so many of them moving into the towns from the countryside to find work in the new industries, but there just weren’t enough houses or jobs for them all. Workhouses were partly a result of all that.

What a fascinating piece of history, Millie. Thank you for this interesting post and your photographs. As bad as it was, the workhouse had saved lives, especially in the winter time. I wouldn’t judge the idea of workhouses from my today’s perspective: in that era, there were many people whose living conditions were as bad ( if not worse) as the ones in the workhouse.

You’re right, Inese. Many of the really destitute would have died if not for workhouses. Having moved to find work in the industries springing up in the towns and cities, thousands had left the countryside (where life had been hard, anyway) to find that no housing or jobs were available for so many. So they faced starvation as well as homelessness – as you say, fatal during the winter months.

I think it was the fact that conditions in workhouses were so hard to bear (e.g.families being split up and the hard toil from morning to night, that gave the workhouses such a bad name. Then there was the stigma of it all, as well as the feeling of being kept from society, as though they were in prison.)’ But at least, workhouses kept most ‘inmates’ alive. Expert have looked at the daily dietary rations and concluded that they were ‘adequate’, but lacking in Vitamin C. It’s a fascinating topic, albeit a sad one.

Yes, absolutely fascinating. I think that it is important to understand that the workhouses were not built to exploit people, to use their social status. That was an attempt to provide a solution.

Thanks for an interesting post Millie. 🙂 I had once started reading Oliver Twist in school but it made me sad and I left the book.

What a sad story the place would have to tell?

Thanks Norma. Sorry for the late reply but I’m hardly on my blog at he moment. (I’m trying to focus on my book I have so many posts to be written up, too!)

Many of Dickens’ stories are sad, especially when the very poor were involved. The Victorian ear was not an easy one for the poor, and there were so many diseases around, too, like typhoid, cholera and consumption (TB). Workhouse walls must hold some sad tales, I think. 😀

🙂

Thank you for your stories Millie!! ( sorry to be so behind) yes, Oliver Twist, A Christmas Carol- “are there no workhouses?… We really have a sad history of our treatment of other human beings.

Hi Cybele. Please don’t apologise for being behind! I couldn’t be more so if I tried. This was my first post for a month. We’d visited The Workhouse for a second time lately and it was on my mind, so I just had to write it up. I already had dozens of posts waiting to be written before it, so this one really queue jumped! Like you, I’ll need to play’catch up’ soon.

I appreciate your thoughtful comment. Oliver Twist always comes to mind when we think of workhouses, as he was in one when he asked for more gruel. Most workhouses were very sad places.

So very interesting as well as sad. Even the best intentions can go bad, I suppose. Thanks for the great tour, pictures, and information on the workhouses. Enjoyed it.

Thanks Jack. So sorry for this very late reply. I’ve been avoiding my blog for a while because I’m trying to finish Book 3 at the moment. I have lots of posts to write up but they will just have to go ‘on hold’ for a while. I imagine yours is well on the way to publication by now? Best of luck with it when you do.

No problem on the reply time, milliethom. I fully understand. Happy to hear about your Book 3 moving forward as is mine though not quite ready for publication just yet. Thank you for the best wishes and same to you. Can’t wait for your Book 3 to be added to 1 and 2 in my collection. Great reads!

Lovely to hear from you, Jack. I’m looking forward to reading your next book, too – which I think will be finished well before mine. Time just seems to fly nowadays and I’m getting nowhere fast! 😀

A great piece, photos included. I’ve always been moved by Dickens’ depictions of the poor and needy.

Thanks Anna. Dickens gave us so much information about life in the Victorian era, depicting the lives of the poorest people in society in particular. ‘Oliver Twist’ and ‘A Christmas Carol’ always spring to mind. Workhouses were pretty grim, but the alternative in many cases was starvation.

An excellent post. Louise sent me over here. It is interesting to see how different it is now than when I visited soon after the opening. Then, only the Women’s Refuge was furnished.

Thanks Derrick! Our first visit was over ten years ago and even then, the rooms were mostly empty. Many still are, but the NT are gradually adding pieces of suitable furniture. There’s a big push at the moment to get much more in, so I’m expecting to see some big changes next time I visit.

Great post!

Thanks, Murielle. I don’t know how I managed to miss your comment. The Workhouse certainly brings everything Dickens said about such places to mind. It was a hard life for ‘inmates’.

Thanks Murielle.The Workhouse is definitely an interesting place to visit.

We popped into Southwell specifically to visit the Minster and didn’t have time to see the workhouse. I didn’t realise how extensive it is/was. Fascinating article, Millie – and so thorough – as usual!

Thanks, Mike! It’s a pity you didn’t get to the Workhouse but the Minster’s well worth a visit, too. Southwell has a few points of historical interest for visitors. One is connected to the Civil War. It was at the Saracen’s Head pub in the town (formerly the King’s Arms) that Charles I surrendered to the the Scot in 1646.

What a sad and grim place! But it is history nonetheless. I have been trying to research one side of my family history. ( in a Prussian/Polish area). One chap was born around 1830 and there is no record of his parents. He lists nothing on any documentation, immigration, marriage, death etc.He was trained as a weaver in an area renowned for textile production. I am thinking that a workhouse such as this was just where he might have grown up. If so, it is doubtful that he would have any knowledge of who his parents were. Millie, do you know if workhouses were a feature of early 1800 European society as well?

I haven’t come across references to any workhouses outside of England, Wales and Ireland. If I remember correctly, Scotland had its own system of poorhouses and Canada had poorhouses linked to farms, on which poor people could work. I know of none across mainland Europe.

In England, the main area for weaving in Victorian times was West Yorkshire (spinning was more in Lancashire). There were workhouses in Yorkshire. Offhand, I know of one at Ripon and another at Thirsk – but there are probably others.

Workhouses in England were basically a response to the thousands of poor who had moved into the towns looking for jobs during the Industrial Revolution. So many thousands of people resulted in insufficient housing and jobs. The growing textile industry was a big part of industrialisation, so it’s possible the man you’re looking for grew up in a workhouse. I’ve a feeling some of the earliest workhouses/poorhouses in England were opened around the time you mention (early 1800s) but, as I said, I’ve never heard of any in mainland Europe. But I haven’t researched that, so I could well be eating my words if your research proves differently.

You’ve given yourself some interesting research to do, Amanda! I know that, like me, you enjoy it, even though it can be frustrating at times!

That is very interesting information, Millie. Thank you so much. I feel sure that the workhouses operated in Europe albeit in perhaps a slightly different form. I know that some of my poverty stricken ancestors worked and lived at factories that produced textiles in Denmark, and there was ” fattiglem” … homes for the old and infirm so I assume perhaps orphan children might also have been catered for in these places. Some of my ancestors young siblings born out of wedlock, were fostered out to farms in the rural areas, and did not return to their own family, and of course, once they had were older, they were on their own. In Australia, being so British in many =bureaucratic ways 😉 we had workhouses too, and the convict women or emancipated poor women lived there working. Even as late as 1922, my great grandmother was placed in a benevolent asylum on an island off the coast, where the old, infirm and unwanted people went. They had to work and made their own bedding etc…. it seems very harsh to look back on, but I think it was infinitely better than roaming the streets. What an cataclysmic impact the industrial revolution had on society.

Thanks for the link to your post. I knew a lot about the long history of Poor Laws, but had never seen such great photos of Southwell before.

Hels

Art and Architecture, mainly

http://melbourneblogger.blogspot.com/2022/11/british-workhouses-charity-or-prison.html

Hi. Sorry for not replying sooner but I haven’t been on my blog for a while. I just clicked on your link on Twitter. Thank you for liking my photos! They were taken a few years ago now.