Last August, Nick and I spent some time up in the North of England in order to visit one of my all-time favourite sites . . . Hadrian’s Wall. I’m totally smitten by this structure and the wonderful, open scenery around it, but I can well imagine what the Romans felt about manning it, particularly in the cold, wet, or icy winter months. It really is quite desolate up there, with nothing to see for miles other than the odd farm and plenty of sheep.

We took lots of photos of the various forts and museums, as well as several of the Wall itself. I thought I’d do the first post about Hadrian’s Wall in general and follow it with a couple about the forts we visited along its route. To start with, here’s some information about the Roman Invasion and the building of the Wall:

The Romans first invaded Britain in 55 BC under Julius Caesar, but this was not a success, and permanent occupation of the island only began in AD 43 when the Emperor Claudius launched an invasion…

Even then, the invasion was not as easy as Claudius had hoped. The Celtic tribes were savage and warlike and most had no intention of succumbing to Roman domination. Some did, of course, including the Brigantes – whose queen, Cartimandua, I mentioned in my Chester post. It was only once the Boudicca uprising of AD 60-61 had been quelled that the Romans were able to move out and establish control over the rest of the country.

The fort of Roman Chester (Deva) was established by AD 70. The great fortress at York, Eboracum – which became the provincial capital of ‘the North’ – was also founded at this time, and shortly after AD 100 the most northerly army forts stretched between the Tyne and the Solway. These were linked by a road now known as the Stanegate, which provided good communications between Corbridge towards the east and Carlisle in the west. It was along this line that, in AD 122, the Emperor Hadrian ordered the construction of the Wall.

Hadrian’s Wall is the most important monument built by the Romans in Britain. For 300 years it was the north-west frontier of the Roman Empire. According to Hadrian’s biographer, it was intended to separate Romans from the barbarians further north. But in many ways, the Wall is the recognition of Rome’s abandonment of its intentions to conquer all of Britain. Having originally intending to conquer further north the Romans had now become more interested in controlling goods in and out of their empire and focused on their frontiers.

Hadrian’s Wall stretched for 73 miles (80 Roman miles) across country, from Bowness-on-Solway in the west to Wallsend-on-Tyne in the east, and forts were located about every five Roman miles. It followed the natural contours of the Whin Sill Ridge:

It was built by the soldiers themselves, mostly the legionaries:

The Wall is thought to have been up to 3.1 meters thick and about 4-5 meters high. At the top was probably a protected walkway for soldiers on patrol. At first, it was built either of stone or, in the western third, of turf and timber and replaced by stone after 30 years.

Milecastles were gateways, placed at every mile between the forts, as legal crossing points:

Turrets, or small watch towers, were built into the wall at intervals of a third of a Roman mile (equivalent to 541 yards) i.e. two turrets between each milecastle. The reconstructions below are from Vindolanda (the site of one of the forts along the Stanegate road, already in existence before the Wall was built.):

Below is a reconstruction of a Roman soldier on watch over the Wall – probably at one of the milecastles or turrets. It wasn’t the most pleasant of jobs during the cold northern winters – especially for soldiers used to Mediterranean climes.

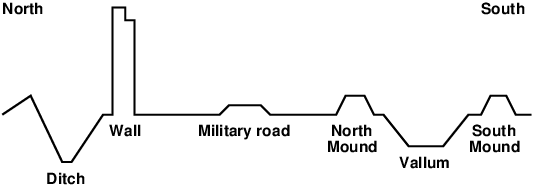

During the building of the Wall, it was decided to build an additional 12 or 13 forts actually on the wall line. South of the Wall, a great earthwork known as the Vallum was completed. This consisted of a ditch with a mound set back on either side stretching the length of the frontier from the Tyne to the Solway. Crossings through the Vallum were only at the forts. There was also a ditch on the northern side, except in places where the high ridge or the Solway coast made it unnecessary. Material from this ditch was used to make an outer band on the north side.

Soldiers from three legions of Britain (Legionaries) came north to build the Wall, with soldiers from the provincial army (Auxilliaries) and even sailors from the fleet to help. In the ‘overbright’ picture below from The Roman Army Museum, the Auxilliary soldier is the one with the oval-shaped shield:

It took them over ten years to complete. But on Hadrian’s death in AD 138, his wall was abandoned on the orders of the new emporer, Antoninus Pius, who ordered the building of a new wall almost 100 miles further north, acoss what is now known as the Central valley of Scotland. It stretched for 37 miles, from the Forth to the Clyde estuaries and, unsurprisingly, became known as the Antonine Wall. After 20 years, it was abandoned in favour of a return to Hadrian’s Wall.

Outside of the forts, civil settlements (vicus) became established, where the soldiers’ families lived. There were also shops and inns in these settlements, seeking to make a living from the soldiers, who were relatively well paid compared to the farmers of the frontier region. l’ll say more about these settlements in my next two posts.

Since the Roman withdrawal from Britain in AD 410, Hadrian’s Wall has gradually reduced in size due to local people plundering the stones, for a variety of purposes. Many churches, farms and field walls, as well as several castles contain stones originally found in the Wall. Plundering continued until the 19th century when archaeological excavations began and interest in the preservation of heritage sites took on an importance. The agricultural revolution of the 18th century also led to further destruction of the Wall as the land was cultivated. Today, although the actual Wall has disappeared in places, it survives in place-names such as Wallsend, Heddon-on-the-Wall and Walton – amongst several others.

I have visited most of the forts along the Wall, as well as The Roman Army Museum at Carvoran. There are several sites I really like, but intend to do posts only about a couple of them. Each site has something different to offer. To finish with, here’s a photo of a Roman Legionary we met at Birdoswald Roman Fort. He was very chatty and friendly and put on his special scowl just ‘for the camera’: